Equations & Transformations

3x3 Matrices

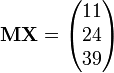

For 3x3 matrices and upward, the process of finding the determinant and inverse is considerably more convoluted. We will take the following example matrix:

- Determinant

- 1. Choose any row or column of the matrix. For the example, we'll choose the last row.

- 2. Take the first element in the row and imagine deleting the column and row it's in. This leaves you with a submatrix:

- 3. Find the determinant of this submatrix, as above. In our case, the determinant of the submatrix is

-

- ( − 1 * 4) − (3 * − 1) = − 4 − ( − 3) = − 1

- 4. We now repeat steps 2 and 3 for the second and third elements of our chosen row:

-

- Deleting row 3 and column 2 we obtain the submatrix:

-

-

-

- The determinant is -2.

-

-

-

- Deleting row 3 and column 3 we get:

-

-

-

- The determinant of this is 1.

-

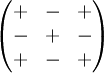

- 5. Now we have to change the signs of some of these determinants in order to obtain values known as the cofactors of the original matrix. To do this, we recall the following matrix:

-

- This tells us that if we chose the first or last row in step 1, we keep the sign of the first determinant we found; we reverse the sign of the second; and we keep the sign of the last. Our three determinants were -1, -2 and 1. The cofactors are therefore -1, 2 and 1.

- 6. The cofactor of -1 came from the element 2 in the bottom left; the cofactor 2 came from the element 2 at the bottom centre; and the cofactor 1 came from the element 1 at the bottom right. What we do now is to multiply each cofactor by the element from which we got it and add up the results:

-

- ( − 1 * 2) + (2 * 2) + (1 * 1) = − 2 + 4 + 1 = 3

- 7. The determinant is 3.

- Inverse

To find the inverse of a 3x3 matrix, we start off by following through our method above to find the cofactors for all of the elements in the matrix.

To reiterate, for every element of the matrix:

- Delete the row it's in and delete the column it's in to obtain a 2x2 submatrix.

- Find the determinant of the submatrix.

- Change its sign as necessary.

-

- The formal method of changing the sign is to multiply the determinant by -1i+j where i is the row number and j is the column number of the element you selected. For example, with the top-left element, we get the submatrix:

-

- The determinant of this matrix is -9. The row number was 1 and the column number was 1, so we do -9 x -11+1 = -9 x 1 = -9.

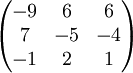

When you have found all of the cofactors, you can put them in a 3x3 matrix. For our example matrix, we get:

- 4. To check that you have obtained the correct matrix of cofactors, you can take any row or column and multiply each element in it by the corresponding element in the original matrix, and add these up; you should get the determinant, regardless of which row or column you choose. Another property of the matrix of cofactors is that if you multiply each element in a row/column by the corresponding element in a different row/column, and add these numbers up, it will come out as zero.

- 5. This is helpful to us because remember that if we multiply the original matrix by its inverse, we get the identity matrix. If we transpose the matrix of cofactors then the rows become the columns and the columns become the rows:

-

- Notice where each of the elements have moved.

-

- The resulting matrix is called the adjugate or adjoint of the original matrix. If we multiply this matrix by the original, notice what we get:

-

- As you can see, when we multiply the first row by the first column, as we do in matrix multiplication, we are doing the same that we were when we multiplied the first column of the matrix of cofactors by the first column of the original matrix - and remember that we obtained the determinant. When we multiply the first row of the adjugate by the second column of the original, we are doing the same as we were when we multiplied the first column of the matrix of cofactors by the second column of the original - i.e. multiplying by an alien column. Like before, we get zero.

-

- Recall that if we multiply the inverse of a matrix by that matrix we should get the identity matrix. So far we have got a matrix similar to the identity matrix but 3 times large - that is, larger by a factor of the determinant. So now we can easily conclude the process and obtain the inverse.

- 6. The inverse of the original matrix is the adjugate multiplied by the inverse of the determinant. In our case, this is:

It is far more usual to keep the inverse of the determinant outside the matrix, since it would be less elegant if we carried through with the multiplication:

- Solving Systems of Equations

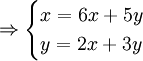

Suppose you are presented with the following simultaneous equations.

x − y + 3z = 11

2x − y + 4z = 24

2x + 2y + z = 39

We can put the coefficients of the variables into a matrix, and represent the problem like this:

If we call the matrix of coefficients M and the matrix of the variables X, then we can say:

Rearranging for X:

We can use the inverse matrix we found in the last section to solve these equations:

If the determinant of the matrix of coefficients is zero, then the matrix has no inverse for obvious reasons; the matrix is said to be singular if the determinant is zero. In this case, the equations have no unique solution - that is, there might be more than one solution or there might be no solutions at all. (If there is a solution or if there are many solutions, the system is said to be consistent.)

Matrices as Transformations

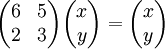

Matrices represent linear transformations. For every linear transformation, there is exactly one equivalent matrix, and every matrix represents a unique linear transformation. To work out the matrix for a particular transformation, form and solve an equation as in the following example:

To find the matrix corresponding to the reflection in the x-axis, the point (x,y) will be transformed to (x,-y), thus:

where M is the matrix we want to find. Assuming we are dealing with a two-dimensional plane, M must be of the form:  and so:

and so:

As we want this to apply for all points (x,y), x and y must be independent of one another. This means that both b and c must be 0 and so we get:

a = 1 and d = -1, so the matrix for reflection in the x-axis is:

An alternative to this method is as follows:

- Find the transformation of the point (1,0). In this example, the reflection of (1,0) in the x-axis is just (1,0). Call this point (x1,y1).

- Find the transformation of the point (0,1). In this example, it's (0,-1). We'll call this point (x2,y2).

- The matrix you seek is then:

- Invariance

An invariant point is one which is left unchanged by a transformation, i.e.:

Some transformation matrices only have one invariant point, whilst some will have a line of invariant points. It should be noted that under the identity matrix all points are invariant, and that the point (0,0) is invariant under all transformation matrices.

A line of invariant points is where all points on a certain straight line are invariant for a specific matrix, e.g.:

Find the equation of the line of invariant points for the transformation

For the point (x,y) to be invariant it must satisfy:

Since these are the same equation, there must be a line of invariant points:

This shows that if y is equal to -x, then the point (x,y) will be invariant, so any point on the line y = − x is an invariant point.

It is also possible to have a line which is unchanged by a transformation, but the points on the line may change positions, i.e. any point on a certain straight line will still be on the same straight line after the transformation even if the actual point has changed. For example: under the matrix representing reflection in the y-axis, any horizontal line will remain unchanged, but the points on the line will not, i.e. (1,0) will be mapped to (-1,0) but both points remain on the line y = 0.

An invariant line can be found like so:

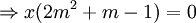

Usually, the +c can be ignored, as the point (0,0) will always be mapped to (0,0) and so c must be 0. Example, if M =

So either x = 0 (the origin is always invariant), or 2m2 + m − 1 = 0

So either  or m = − 1, thus there are two invariant lines:

or m = − 1, thus there are two invariant lines:

Comments

Post a Comment